Indigenous History

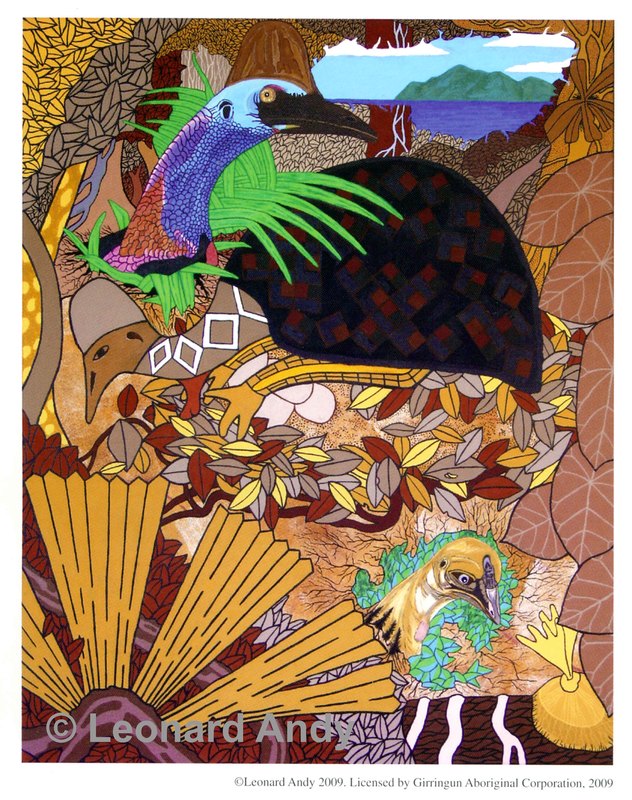

Artwork above by C4 Indigenous Coordinator Leonard Andy

History of the Indigenous People of the Cassowary Coast

|

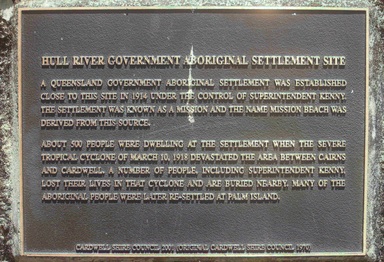

The Hull River Aboriginal Settlement

The Origins of the " Mission" The Hull River Aboriginal Settlement which operated from 1914 until it was destroyed by a severe tropical cyclone in 1918, was a Queensland Government settlement covering over 2900 acres of land. It was never a mission in a religious sense, although the name "Mission Beach" was derived from the Aboriginal settlement here which was referred to by local community members as " The Mission". There were few European settlers in this area at the time, such as the Cuttens at Bingil Bay, Garner at Garners Beach. It was only in 1912 that permanent residence was taken up by selectors at what was later known as South Mission Beach (the Reids, Ben Beamon and George Webb). Following the 1897 Queensland Act for the Protection of Aboriginals and the Restriction of the sale of Opium, this reserve was planned and set up by the state government. In those times culture conflict was inevitable due to the spread of colonial settlement after the founding of Cardwell in 1864. Settlers appropriated the land and hunting grounds of Aboriginal people but also wanted cheap Aboriginal labour on their selections, sometimes paying with rum. Chinese banana growers along the Tully River supplied opium in return for work. These contributed to social problems for which the Hull River settlement was to be the answer by relocating Aboriginal people to this remote reserve. |

|

Many Aboriginal people of the district had a great fear of being removed to the settlement, some hiding in the rainforested mountains for months to avoid being taken there. Most removals were forced and arrests were effected by the police. For example, in May 1915 near Cardwell, the mounted police surrounded a camp and took the people to the lock-up in Cardwell and from there by launch to the Hull. A few people did go voluntarily, to join family who had been taken there, but deserting was also common.

The History of the Settlement The settlement was established in 1914 a mile or so north of the Hull River mouth, on a hill overlooking the northern end of the beach. A Superintendent, John Martin Kenny, was appointed and scrub-falling, clearing and fencing commenced. Two administration houses were built, as well as stores and stockyard. |

At the close of 1915 there were established 4 acres of citrus trees, 11 acres of bananas and 10 acres of pumpkins. By 1918 there were

6,000 banana plants, several hundred citrus and other fruit trees and also tobacco and coffee. A few milking cows and working horses were the only stock. The Community was quite remote. A rough bridle track linked the Hull River to Banyan (forerunner of Tully) and other

access was by sea. When a telephone line was proposed from the settlement to Banyan, the track had to be cleared through the swamp and scrub and the line erected. It was completed just before the fateful cyclone of 1918.

6,000 banana plants, several hundred citrus and other fruit trees and also tobacco and coffee. A few milking cows and working horses were the only stock. The Community was quite remote. A rough bridle track linked the Hull River to Banyan (forerunner of Tully) and other

access was by sea. When a telephone line was proposed from the settlement to Banyan, the track had to be cleared through the swamp and scrub and the line erected. It was completed just before the fateful cyclone of 1918.

|

The People of the Hull River Settlement

The Djiru People The Hull River area lies within the traditional tribal territory of the JiDjiru speaking Aboriginal people who were close neighbours linguistically and culturally to the Jirrbal, Gulngay and Mamu speaking people of the adjacent rainforests There were probably less than a fifth of the original people still in the area when the settlement opened. As well as the local people, Aborigines were brought to the settlement from close by and further afield, as Police and State government records show. People Brought to the Settlement As the settlement became established, more people were brought to live there. In 1914, 41 Aboriginal people were brought in, many of them local. By the end of 1915, the Aboriginal population was about 400, including many from other districts, for example, 20 from Mourilyan and 159 from the Tully and Murray Rivers. In 1916, 82 Aboriginal people were removed here for "disciplinary reasons for their relief and protection", from Thursday Island, Cooktown, Chillagoe, Atherton, Ayr, Hughenden, Ukalanda and Stewart's Creek. By 1916 there were about 490 Aboriginal people at the settlement. Some 200 died during 1917 when malarial fever ravaged the area so that by March 1918 there were approximately 300 people dwelling there. |

The Superintendent

The Superintendent, John Martin Kenny, had been for some years a non-Commissioned officer of Native Police at Cooktown, an overseer in charge of the McIvor River (Cape Bedford Mission) and later was employed in the north as an engineer. It was he who chose the site for the settlement buildings, exposed to the full force of the onshore winds, which proved a terrible mistake when the 1918 cyclone crossed the coast.

Life at the Settlement

The Superintendent and his family lived in a bungalow on the hillside, and there were a couple of cottages for the Assistant Superintendent and storekeeper. The stores, harness and tool sheds, and water tanks for fresh water were also on the hillside. The Superintendent's

son taught school pending the appointment of a teacher and there were regular visits by a government medical officer and nursing attendant.

The Aboriginal people lived in ti-tree bark dwellings largely along the beach front. They worked for the settlement, which produced bananas for the southern markets or worked for other employers under agreements. The food provided at the settlement was usually flour, sugar and tea and sometimes corned beef. There was a big boiler at the foot of the hill where they boiled tea and served it up to the people who took their billy-cans there. The Aboriginal people had to supplement the food provided with bush tucker (which was difficult as there were so many people in the area) with fishing and turtle-catching trips when the administrators lent the boat.

A number of the people deserted the settlement when the opportunity came and then had to hide from the police to avoid being returned, or being sent to another reserve even further away.

The Cyclone of 1918

The Devastation

On Sunday, 10 March 1918, an extremely intense, severe tropical cyclone crossed the North Queensland Coast near Innisfail. Pressure at Innisfail reached 27.35 inches and almost every building in the town was flattened. Winds of 240-288 km/hour battered the area. Over 305 mm (12 inches) of rain fell on that Sunday, with the eye passing close to the Hull River at about 10 pm. Many trees were uprooted and strewn on the ground, broken or bent right over and those remaining were stripped of leaves.

The Superintendent's house and those of his Assistant and of the Officer in charge of the boats were totally destroyed. Toilet blocks were demolished but the retail and flour store withstood the devastation. Kenny and his daughter were killed by wreckage hurled by the wind as they struggled from the destruction of their house.

The storm surge along the coast was the highest known at that time, thought to have been around 12 feet (about 3.7m) in height. Almost all the huts and humpies on the beach were destroyed. Several people were swept away and drowned. All the boats at the settlement were destroyed by the huge seas. It was a night of hopeless misery and dejection as people, battered by debris, tried to shelter from the wind and rain behind ruined buildings.

The Superintendent, John Martin Kenny, had been for some years a non-Commissioned officer of Native Police at Cooktown, an overseer in charge of the McIvor River (Cape Bedford Mission) and later was employed in the north as an engineer. It was he who chose the site for the settlement buildings, exposed to the full force of the onshore winds, which proved a terrible mistake when the 1918 cyclone crossed the coast.

Life at the Settlement

The Superintendent and his family lived in a bungalow on the hillside, and there were a couple of cottages for the Assistant Superintendent and storekeeper. The stores, harness and tool sheds, and water tanks for fresh water were also on the hillside. The Superintendent's

son taught school pending the appointment of a teacher and there were regular visits by a government medical officer and nursing attendant.

The Aboriginal people lived in ti-tree bark dwellings largely along the beach front. They worked for the settlement, which produced bananas for the southern markets or worked for other employers under agreements. The food provided at the settlement was usually flour, sugar and tea and sometimes corned beef. There was a big boiler at the foot of the hill where they boiled tea and served it up to the people who took their billy-cans there. The Aboriginal people had to supplement the food provided with bush tucker (which was difficult as there were so many people in the area) with fishing and turtle-catching trips when the administrators lent the boat.

A number of the people deserted the settlement when the opportunity came and then had to hide from the police to avoid being returned, or being sent to another reserve even further away.

The Cyclone of 1918

The Devastation

On Sunday, 10 March 1918, an extremely intense, severe tropical cyclone crossed the North Queensland Coast near Innisfail. Pressure at Innisfail reached 27.35 inches and almost every building in the town was flattened. Winds of 240-288 km/hour battered the area. Over 305 mm (12 inches) of rain fell on that Sunday, with the eye passing close to the Hull River at about 10 pm. Many trees were uprooted and strewn on the ground, broken or bent right over and those remaining were stripped of leaves.

The Superintendent's house and those of his Assistant and of the Officer in charge of the boats were totally destroyed. Toilet blocks were demolished but the retail and flour store withstood the devastation. Kenny and his daughter were killed by wreckage hurled by the wind as they struggled from the destruction of their house.

The storm surge along the coast was the highest known at that time, thought to have been around 12 feet (about 3.7m) in height. Almost all the huts and humpies on the beach were destroyed. Several people were swept away and drowned. All the boats at the settlement were destroyed by the huge seas. It was a night of hopeless misery and dejection as people, battered by debris, tried to shelter from the wind and rain behind ruined buildings.

The Aftermath of the Cyclone

Help reached the settlement by sea when the Innisfail from Townsville reached Dunk Island on March 14. A party struggled through the devastated scrub from the Hull to Banyan and a telegraph message was sent to Cardwell. Police Sergeant O'Regan walked 30 miles along the beach, swimming across swollen rivers to get there.

The injured had to be attended to and the bodies of the dead had to be buried. The pregnant Mrs. Kenny was injured and she was sent to Townsville on a passing steamer. The Government Medical Officer did not arrive until March 31 to treat 50-60 minor injuries and 5 serious cases.

Temporary shelters were rigged up and the people who had survived and not deserted the settlement had to make the best of it. They had tinned foods from the store and they roasted green bananas. In the tops of several Casuarina trees were found salvageable bags of flour and a case of jam, among other things.

Burials

Many people were killed by flying debris and buildings which collapsed as they tried to shelter in them. Estimates vary, with official reports concluding that 12 died, but it is more likely that about 50 Aborigines died and were buried at the site. Accounts differ on the exact location of the graves but they seem to have been close to the beach. Kenny and his daughter were buried separately on the crest of the hill near their house.

Where the People Went

Many of the Aboriginal people fled to the bush when the cyclone approached and some may have died there from injuries or from exposure. The survivors who remained at the site were to learn that the government had decided not to rebuild the settlement. The Government Health Inspector who visited the area in 1918 recommended that Great Palm Island, 37 miles off the coast north-east of Townsville, be designated a reserve for Aboriginal people to replace the Hull River Settlement (as it was free of malarial swamps and had abundant fresh water).

The remaining people still at the Hull River were put on boats and taken to Palm Island, commencing June 1918, whether they wished to go or not. Those who had taken to the bush were rounded up by the Police and removed to Palm Island. Aboriginal people continued to be taken from Cardwell district to Palm Island for many more years subsequently.

Help reached the settlement by sea when the Innisfail from Townsville reached Dunk Island on March 14. A party struggled through the devastated scrub from the Hull to Banyan and a telegraph message was sent to Cardwell. Police Sergeant O'Regan walked 30 miles along the beach, swimming across swollen rivers to get there.

The injured had to be attended to and the bodies of the dead had to be buried. The pregnant Mrs. Kenny was injured and she was sent to Townsville on a passing steamer. The Government Medical Officer did not arrive until March 31 to treat 50-60 minor injuries and 5 serious cases.

Temporary shelters were rigged up and the people who had survived and not deserted the settlement had to make the best of it. They had tinned foods from the store and they roasted green bananas. In the tops of several Casuarina trees were found salvageable bags of flour and a case of jam, among other things.

Burials

Many people were killed by flying debris and buildings which collapsed as they tried to shelter in them. Estimates vary, with official reports concluding that 12 died, but it is more likely that about 50 Aborigines died and were buried at the site. Accounts differ on the exact location of the graves but they seem to have been close to the beach. Kenny and his daughter were buried separately on the crest of the hill near their house.

Where the People Went

Many of the Aboriginal people fled to the bush when the cyclone approached and some may have died there from injuries or from exposure. The survivors who remained at the site were to learn that the government had decided not to rebuild the settlement. The Government Health Inspector who visited the area in 1918 recommended that Great Palm Island, 37 miles off the coast north-east of Townsville, be designated a reserve for Aboriginal people to replace the Hull River Settlement (as it was free of malarial swamps and had abundant fresh water).

The remaining people still at the Hull River were put on boats and taken to Palm Island, commencing June 1918, whether they wished to go or not. Those who had taken to the bush were rounded up by the Police and removed to Palm Island. Aboriginal people continued to be taken from Cardwell district to Palm Island for many more years subsequently.

The Hull Site

Ron Fleger's beach house in the 1940s.

The Hull River site was cleared of materials that could be used on Palm Island and then abandoned. White settlers took up parts of the area, roads were improved and development slowly commenced. The township which was surveyed off in 1938 was named Kenny but it was known locally as South Mission Beach and officially recognized by that name from 1967.

The Banfields and Dunk Island

In 1897, E.J. Banfield, on doctor's advice, gave up his job as a Townsville journalist, and settled on Dunk Island with his wife Bertha, until his death in 1923. While on the island they grew fruit and vegetables, kept poultry and goats, contemplated the natural environment, and studied the legends and customs of the Aboriginal people. Banfield recorded his discoveries in several books that he wrote at that time.

South Mission Beach

After the sugar mill was built in Tully in 1932, people began to use South Mission Beach for camping and building holiday shacks. Getting to and from the beaches was still difficult.

The Banfields and Dunk Island

In 1897, E.J. Banfield, on doctor's advice, gave up his job as a Townsville journalist, and settled on Dunk Island with his wife Bertha, until his death in 1923. While on the island they grew fruit and vegetables, kept poultry and goats, contemplated the natural environment, and studied the legends and customs of the Aboriginal people. Banfield recorded his discoveries in several books that he wrote at that time.

South Mission Beach

After the sugar mill was built in Tully in 1932, people began to use South Mission Beach for camping and building holiday shacks. Getting to and from the beaches was still difficult.